A következő címkéjű bejegyzések mutatása: DC-10. Összes bejegyzés megjelenítése

A következő címkéjű bejegyzések mutatása: DC-10. Összes bejegyzés megjelenítése

An Analysis of McDonnell Douglas’s Ethical Responsibility in the Crash of Turkish Airlines Flight 981

Download it:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B8aiechh7K6ickQwV1NzWnBnbXc/view?usp=sharing

[Final report] TK 981

Download it:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B8aiechh7K6ic21pUURxREpUVFU/view?usp=sharing

TK 981

|

| Complete destruction in the Ermenonville forest |

The crash was caused when an improperly secured cargo door at the rear of the plane broke off, causing an explosive decompression which severed cables necessary to control the aircraft. Because of a known design flaw left uncorrected before and after the production of DC-10s, the cargo hatches did not latch reliably, and manual procedures were relied upon to ensure they were locked correctly. Problems with the hatches had occurred previously, most notably in an identical incident that happened on American Airlines Flight 96 in 1972. Investigation showed that the handles on the hatches could be improperly forced shut without the latching pins locking in place. It was noted that the pins on the hatch that failed on Flight 981 had been filed down to make it easier to close the door, resulting in the hatch being less resistant to pressure. Also, a support plate for the handle linkage had not been installed, although manufacturer documents showed this work as completed. Finally, the latching had been performed by a baggage handler who did not speak Turkish or English, the only languages provided on a warning notice about the cargo door's design flaws and the methods of compensating for them. After the disaster, the latches were redesigned and the locking system significantly upgraded.

Aircraft

|

| McDonnell-Douglas DC-10-10 'Ankara' |

Accident

Flight 981 had flown from Istanbul that morning, landing at Paris's Orly International Airport just after 11:00 am local time. The aircraft was carrying just 167 passengers and 11 crew members in its first leg. 50 passengers disembarked in Paris. The flight's second leg, from Paris to London Heathrow Airport, was normally underbooked, but due to strike action by British European Airways employees, many London-bound travellers who had been stranded at Orly were booked onto Flight 981. 216 new passengers boarded the flight. As a result, the layover

increased from the normal one hour to one hour and thirty minutes. Among them were 17 English rugby players who had attended a France–England match the previous day; the flight also carried six British fashion models, and 48 Japanese bank management trainees on their way to England, as well as passengers from a dozen other countries.

The aircraft left Orly at 12:32 pm, bound for Heathrow. It took off in an easterly direction, then turned to the north to avoid flying directly over Paris. Shortly after the take off, Flight 981 was cleared to FL230 (23,000 ft.), and started turning to the west, towards London. Shortly after 12:40 pm, just after Flight 981 passed over the town of Meaux, the rear left cargo door blew off. The sudden difference between the air pressure in the cargo area and the pressurised passenger cabin above it, which amounted to 2 pounds per square inch or 14 kilopascals, caused a section of the cabin floor above the open hatch to fail and blow out through the hatch, along with six occupied passenger seats attached to the floor section. The fully recognizable bodies of the six passengers who were ejected from the aircraft were found along with the plane's rear hatch, all having landed in a turnip field near Saint-Pathus, approximately 15 kilometres (9.3 miles) south of where the remainder of the plane would crash. An air traffic controller noted that as the flight was cleared to FL230, he had briefly seen a second echo on his radar, remaining stationary behind the aircraft, likely the remains of the rear cargo door.

When the door blew off, the primary as well as both sets of backup control cables that ran beneath the section of floor that was blown out were completely severed. This resulted in the pilots losing the ability to control the plane's elevators, rudder, and Number 2 and 3 engines. The flight data recorder showed that the throttle for Engine 2 snapped shut when the door failed. The loss of control of these key components meant that the pilots lost control of the aircraft entirely.

|

| "...disintegrated into millions of pieces instantly" |

Investigation

The French Minister of Transport appointed a commission of inquiry by the Arrêté 4 March 1974. Because the aircraft was manufactured by an American company, observers from the United States participated. There were many passengers on board from Japan and the United Kingdom, so observers from those countries followed the investigation.

Lloyd's of London insurance syndicate, which covered Douglas Aircraft, retained Failure Analysis Associates (now Exponent, Inc.) to investigate the accident as well. In the company's investigation, Dr. Alan Tetelman noted that the pins on the cargo door had been filed down. He learned that on a stop in Turkey, the ground crews had trouble closing the door. They filed the pins down, reducing them by less than a quarter of an inch (6.4 millimetres), and were then able to close the door effortlessly. It was proven by tests that the door subsequently yielded to about 15 psi (100 kPa) of pressure, in contrast to the 300 psi (2,100 kPa) that it had been designed to withstand.

Cause

|

| Recovered cargo door during the technical examination |

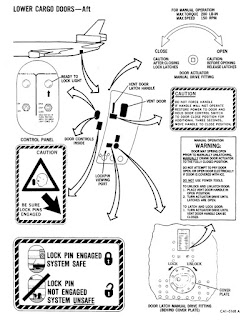

To ensure this rotation was complete and the latches were in the proper position, the DC-10 cargo hatch design included a separate locking mechanism that consisted of small locking pins that slid behind flanges on the lock torque tube (which transferred the actuator force to the latch hooks through a linkage). When the locking pins were in place, any rotation of the latches would cause the torque tube flanges to contact the locking pins, making further rotation impossible. The pins were pushed into place by an operating handle on the outside of the hatch. If the latches were not properly closed, the pins would strike the torque tube flanges and the handle would remain open, visually indicating a problem. Additionally, the handle moved a metal plug into a vent cut in the outer hatch panel. If the vent was not plugged, the fuselage would not retain pressure, eliminating any pneumatic force on the hatch. Also, there was an indicator light in the cockpit, controlled by a switch actuated by the locking pin mechanism, that remained lit unless the cargo hatch was correctly latched.

Similarities American Airlines Flight 96

|

| Cargo door of Flight 96 being observed after landing |

In the aftermath of Flight 96, the NTSB made several recommendations. Its primary concern was the addition of venting in the rear cabin floor that would ensure that a cargo area decompression would equalise the cabin area, and not place additional loads onto the floor. In fact, most of the DC-10 fuselage had vents like these; only the rearmost hold lacked them. Additionally, the NTSB suggested that upgrades to the locking mechanism and to the latching actuator electrical system be made compulsory. However, while the FAA agreed that the locking and electrical systems should be upgraded, it also agreed with McDonnell-Douglas that the additional venting would be too expensive to implement, and did not demand that this change be made.

The plane that crashed as Flight 981, TC-JAV, or "Ship 29", had been ordered from McDonnell-Douglas three months after the service bulletin was issued, and was delivered to Turkish Airlines another three months after that. Despite this, the changes required by the service bulletin (installation of a support plate for the handle linkage, preventing the bending of the linkage seen in the Flight 96 incident) had not been implemented. The interconnecting linkage between the lock and the latch hooks had not been upgraded. Through either oversight or deliberate fraud, the manufacturer construction logs nevertheless showed that this work had been carried out. An improper adjustment had been made to the locking pin and warning light mechanism, however, causing the locking pin travel to be reduced. This meant that the pins did not extend past the torque tube flanges, allowing the handle to be closed without excessive force (estimated by investigators to be around 50 pounds-force or 220 newtons) despite the improperly engaged latches. These findings concurred with statements made by Mohammed Mahmoudi, the baggage handler who had closed the door on Flight 981; he noted that no particular amount of force was needed to close the locking handle. Changes had also been made to the warning light switch, so that it would turn off the cockpit warning light even if the handle was not fully closed.

|

| Aft cargo door placards on a DC-10 |

It was normally the duty of either the airliner's flight engineer or the chief ground engineer of Turkish Airlines to ensure that all cargo and passenger doors were securely closed before takeoff. In this case, the airline did not have a ground engineer on duty at the time of the accident, and the flight engineer for Flight 981 failed to check the door personally. Although French media outlets called for Mahmoudi to be arrested, the crash investigators stated that it was unrealistic to expect an untrained, low-paid baggage handler who could not read the warning sticker to be responsible for the safety of the aircraft.

Aftermath

The latch of the DC-10 is a study in human factors, interface design, and engineering responsibility. The control cables for the rear control surfaces of the DC-10 were routed under the floor. Therefore, a failure of the hatch that resulted in a collapse of the floor could impair the controls. If the hatch were to fail for any reason, there was a very high probability the plane would be lost. To make matters worse, Douglas chose a new type of latch to seal the cargo hatch. This possibility of a catastrophic failure as a result of this overall design was first discovered in 1969, and actually occurred in 1970 in a ground test. Nevertheless, nothing was done to change the design, presumably because the cost for any such changes would have been borne as out-of-pocket expenses by the fuselage's subcontractor, Convair. Although Convair informed McDonnell Douglas of the potential problem, Douglas ignored these concerns, because rectification of what Douglas considered to be a small problem with a low probability of occurrence would have seriously disrupted the delivery schedule of the aircraft, and caused Douglas to lose sales. Dan Applegate was Director of Product Engineering at Convair at the time. His serious reservations about the integrity of the DC-10's cargo latching mechanism are a classic case in engineering ethics.

After the crash of Flight 981, the latching system was completely redesigned. The latches were redesigned to prevent them from moving into the wrong positions in the first place. The locking system was mechanically upgraded to prevent the handle from being forced closed without the pins in place, and the vent door was altered to be operated by the pins, thereby indicating when the pins, rather than the handle, were in the locked position. Additionally, the FAA ordered further changes to all aircraft with outward-opening doors, including the DC-10, Lockheed L-1011, and Boeing 747, requiring that vents be cut into the cabin floor to allow pressures to equalise in the event of a blown-out door.

Similar accidents

An outward-opening cargo hatch is inherently less resistant to blowing open than an inward-opening one, also called a plug door. In flight, the air pressure inside the aircraft is greater than that outside, and pushes outward on the hatch. In the case of a plug door, this actually seals the door more tightly. An outward-opening hatch, however, relies entirely upon its latch to prevent it from opening in flight. This makes it particularly important that the locking mechanisms be secure. Aircraft other than DC-10s have also experienced catastrophic failures of hatches. The Boeing 747 has experienced several such incidents, the most noteworthy of which occurred on United Airlines Flight 811 in February 1989. On Flight 811, the cargo hatch failed, causing a section of the fuselage to fail, resulting in the deaths of nine passengers, who were blown out of the aircraft.

The NTSB's recommendations following the earlier Flight 96 incident, which were intended to decrease the possibility of another hatch failure, were not implemented by any airline. As a result, the NTSB now communicates directly with the FAA regarding the former's recommendations for safety improvements, and the FAA may issue Airworthiness Directives based on those recommendations. However, the FAA is not obligated to act on NTSB recommendations.

Source:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turkish_Airlines_Flight_981

FX 705

On April 7, 1994, Federal Express Flight 705, a McDonnell Douglas DC-10-30 cargo jet carrying electronics across the United States from Memphis, Tennessee to San Jose, California, experienced an attempted hijacking for the purpose of a suicide attempt.

Auburn Calloway, a Federal Express employee facing possible dismissal for lying about his reported flight hours, boarded the scheduled flight as a deadheading passenger with a guitar case carrying several hammers and a speargun. He intended to disable the aircraft's cockpit voice recorder before take-off and, once airborne, kill the crew with hammers so their injuries would appear consistent with an accident rather than a hijacking. The speargun would be a last resort. He would then crash the aircraft while just appearing to be an employee killed in an accident. This would make his family eligible for a $2.5 million life insurance policy paid by Federal Express.

Calloway's plan was unsuccessful. Despite severe injuries, the crew was able to fight back, subdue Calloway and land the aircraft safely. An attempt at a mental health defense was unsuccessful and Calloway was subsequently convicted of multiple charges including attempted murder, attempted air piracy and interference with flight crew operations. He received two consecutive life sentences. Calloway's appeal was successful in having his conviction for interference ruled as a lesser included offense of attempted air piracy.

Hijacker

The 42-year-old Federal Express flight engineer Auburn Calloway, an alumnus of Stanford University, a former Navy pilot and martial arts expert, faced termination of employment over irregularities in the reporting of flight hours. In order to disguise the hijacking as an accident so his family would benefit from his $2.5 million life insurance policy, Calloway intended to murder the flight crew using blunt force. To accomplish this, he brought aboard two claw hammers, two sledge hammers and a speargun concealed inside a guitar case. It is unclear how Calloway planned to crash the plane or dispose of his intended murder weapons. Just before the flight, Calloway had transferred over $54,000 in securities and cashier's checks to his ex-wife. He also carried a note aboard, written to her and "describing the author's apparent despair".

Flight details

Initially, Calloway was the flight engineer on this flight, but he and his crew exceeded the maximum flying hours by one minute the previous day, so the new three-man flight crew consisted of 49-year-old Captain David Sanders, 42-year-old First Officer James Tucker, and 39-year-old flight engineer Andrew Peterson. At the time of the incident, First Officer James Tucker held the position of Captain at Federal Express on the DC-10 and was also a check airman on the type. Aboard Flight 705, Tucker assumed the role of first officer. FedEx Flight 705 was scheduled to fly to San Jose, California with electronic equipment destined for Silicon Valley.

Hijacking

As part of his plan to disguise the intended attack as an accident, Calloway attempted to disable the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) by tripping its circuit breaker. During standard pre-flight checks, Peterson noticed the tripped breaker and reset it before take-off so the CVR was reactivated. However, if Calloway successfully killed the crew members with the CVR still on, he would simply have to fly for 30 minutes to erase any trace of a struggle from the CVR's 30 minute loop. About twenty minutes after takeoff, as the flight crew carried on a casual conversation, Calloway entered the flight deck and commenced his attack. Every member of the crew took multiple hammer blows which fractured both Peterson's and Tucker's skulls, severing Peterson's temporal artery. The blow to Tucker's head initially rendered him unable to move or react but he was still conscious. Sanders reported that during the beginning of the attack, he could not discern any emotion from Calloway, just "simply a face in his eyes". When Calloway ceased his attack with hammers, Peterson and Sanders began to get out of their seats to counter-attack. Calloway left the cockpit and retrieved his spear gun. He came back into the cockpit and threatened everyone to sit back down in their seats. Despite loud ringing in his ear and being dazed, Peterson grabbed the gun by the spear between the barbs and the barrel. A lengthy struggle ensued with the flight engineer and captain as Tucker, also an ex-Navy pilot, performed extreme aerial maneuvers with the aircraft.

|

| The aircraft involved in FedEx's 90's paint scheme |

Tucker pulled the plane into a sudden 15 degree climb, throwing Sanders, Peterson and Calloway out of the cockpit and into the galley. To try to throw Calloway off balance, Tucker then turned the plane into a left roll, almost on its side. This rolled the combatants along the smoke curtain onto the left side of the galley. Eventually, Tucker had rolled the plane onto its back at 140 degrees, while attempting to maintain a visual reference of the environment around him through the windows. Peterson, Sanders and Calloway were then pinned to the ceiling of the plane. Calloway managed to reach his hammer hand free and hit Sanders in the head again. Just then, Tucker put the plane into a steep dive. This pushed the combatants back to the seat curtain, but the wings and elevators started to flutter. At this point Tucker could hear the wind rushing against the cockpit windows. At 530 mph, the elevators on the plane became unresponsive due to the disrupted airflow. Tucker realized this was because the throttles were at full power. Releasing his only usable hand to pull back the throttles to idle, he managed to pull the plane out of the dive while it slowed down.

Calloway managed to hit Sanders again while the struggle continued. Sanders was losing strength and Peterson was heavily bleeding from a ruptured artery. Sanders managed to grab the hammer out of Calloway's hand and attacked him with it. When the plane was completely level, Tucker reported to Memphis Center, informed them about the attack and requested a vector back to Memphis. He requested an ambulance and "armed intervention", meaning he wanted SWAT to storm the plane. When Tucker began to hear the fight increase in the galley, he put the aircraft into a right turn then back to the left.

The flight crew eventually succeeded in restraining Calloway, though only after moments of inverted and near-transonic flight beyond the designed capabilities of a DC-10. Sanders took control and Tucker, who had by then lost use of the right side of his body, went back to assist Peterson in restraining Calloway. Sanders communicated with air traffic control, preparing for an emergency landing back at Memphis International Airport. Meanwhile, after screaming that he could not breathe, Calloway started fighting with the crew again.

Heavily loaded with fuel and cargo, the plane was approaching too fast and too high to land on the scheduled runway 9. Sanders requested by radio to land on the longer runway 36 left. Ignoring warning messages from the onboard computer and using a series of sharp turns that tested the DC-10's safety limits, Sanders landed the jet safely on the runway at well over its maximum designed landing weight. By that time, Calloway was once again restrained. Emergency personnel gained access to the plane via escape slide and ladder. Inside, they found the cockpit interior covered in blood.

Aftermath

|

| Crew reunion recalling the "bloody" flight of FedEx |

The crew of Flight 705 sustained serious injuries. The left side of Tucker's skull was severely fractured, causing motor control problems in his right arm and right leg. Calloway had also dislocated Tucker's jaw, attempted to gouge out one of his eyes and stabbed his right arm. Sanders suffered several deep gashes in his head and doctors had to sew his right ear back in place. Flight engineer Peterson's skull was fractured and his temporal artery severed. The aircraft itself incurred damages in the amount of $800,000 ($1,277,234 when adjusted for inflation).

Calloway pleaded temporary insanity but was sentenced to two consecutive life sentences on August 15, 1995, for attempted murder and attempted air piracy.

On May 26, 1994, the Air Line Pilots Association awarded Dave Sanders, James Tucker and Andrew Peterson the Gold Medal Award for heroism, the highest award a civilian pilot can receive. Due to the extent and severity of their injuries, none of the crew has, so far, been recertified as medically fit to fly commercially.

Although medically unfit to return to commercial aviation, James Tucker returned to recreational flying in his Luscombe 8A.

As of 2015, the McDonnell Douglas DC-10-30 aircraft involved, N306FE, remains in service as an upgraded MD-10 without the flight engineer position, though it is expected to be phased out by 2018.

Source:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federal_Express_Flight_705

Magassági rekorder: La Paz 'El Alto'

Leszállás a világ legmagasabban (4061,5 m) fekvő nemzetközi repülőterére az Aerosur 727-esével...

...ill. távozás a TAB Cargo DC-10-esével:

...ill. távozás a TAB Cargo DC-10-esével:

Impact Erebus

A very rare 1990 documentary detailing the investigative campaign of Captain Gordon Vette..

Air New Zealand Flight 901

|

| Only a huge smudge could be seen at first by the SAR team |

Air New Zealand Flight 901 (TE-901) was a scheduled Air New Zealand Antarctic sightseeing flight that operated between 1977 and 1979. The flight left Auckland Airport in the morning and spent a few hours flying over the Antarctic continent, before returning to Auckland in the evening via Christchurch. On 28 November 1979, the fourteenth flight of TE-901, a McDonnell Douglas DC-10-30 registered ZK-NZP, flew into Mount Erebus on Ross Island, Antarctica, killing all 237 passengers and 20 crew on board. The accident is commonly known as the Mount Erebus disaster.

The initial investigation concluded the accident was caused by pilot error but public outcry led to the establishment of a Royal Commission of Inquiry into the crash. The commission, presided over by Justice Peter Mahon, concluded that the accident was caused by a correction made to the coordinates of the flight path the night before the disaster, coupled with a failure to inform the flight crew of the change, with the result that the aircraft, instead of being directed by computer down McMurdo Sound (as the crew assumed), was re-routed into the path of Mount Erebus. In Justice Mahon's report, he accused Air New Zealand of presenting "an orchestrated litany of lies" and this charge in the end led to changes in senior management at the airline.

The accident is New Zealand's deadliest peacetime disaster. Flight 901, alongside several other related incidents, were highly detrimental to the reputation of McDonnell Douglas DC-10 aircraft within the public. Following the crash, DC-10 aircraft in New Zealand were replaced by Boeing 747s.

Flight and aircraft

|

| Air New Zealand's sightseeing brochure |

The flight was designed and marketed as a unique sightseeing experience, carrying an experienced Antarctic guide who pointed out scenic features and landmarks using the aircraft public-address system, while passengers enjoyed a low-flying sweep of McMurdo Sound. The flights left and returned to New Zealand the same day.

Flight 901 would leave Auckland International Airport at 8:00 am for Antarctica, and arrive back at Christchurch International Airport at 7:00 pm after flying a total of 5,360 miles (8,630 km). The aircraft would make a 45-minute stop at Christchurch for refuelling and crew change, before flying the remaining 464 miles (747 km) to Auckland, arriving at 9:00 pm. Tickets for the November 1979 flights cost NZ$359 per person (equal to about NZ$1,386 in the first quarter of 2013).

Dignitaries including Sir Edmund Hillary

had acted as guides on previous flights. Hillary was scheduled to act

as the guide for the fatal flight of 28 November 1979, but had to cancel

owing to other commitments. His long-time friend and climbing

companion, Peter Mulgrew, stood in as guide.

The flights usually operated at about 85% of capacity; the empty seats, usually the centre ones, allowed passengers to move more easily about the cabin to look out of the windows.

The aircraft used on the Antarctic flights were Air New Zealand's eight McDonnell Douglas DC-10-30 trijets. The aircraft on 28 November was registered ZK-NZP. The 182nd DC-10 to be built, and the fourth DC-10 to be introduced by Air New Zealand, ZK-NZP was handed over to the airline on 12 December 1974 at McDonnell Douglas's Long Beach plant. It was the first Air New Zealand DC-10 to be fitted with General Electric CF6-50C engines as built, and had logged 20,750 flight hours prior to the crash.

Accident

(All times are as at McMurdo Base: New Zealand Standard Time; UTC+12. Mainland New Zealand was running on New Zealand Daylight Time (UTC+13) at the time of the crash.)

Circumstances surrounding the accident

Captain Jim Collins and co-pilot Greg Cassin had never flown to Antarctica before, but they were experienced pilots and were considered qualified for the flight. On 9 November 1979, 19 days before departure, the two pilots had attended a briefing in which they were given a copy of the previous flight's flight plan.

|

| Expected and actual track of the flight |

Unknown to Captain Collins at the time of the briefing, the flight plan coordinates transcribed into Air New Zealand's ground computer differed from the route flight plan approved in 1977 by the New Zealand Department of Transport Civil Aviation Division. The approved flight plan was along a track directly from Cape Hallett to the McMurdo non-directional beacon (NDB), which, coincidentally, entailed flying almost directly over the 12,448-feet peak of Mount Erebus. However, the printout from Air New Zealand's ground computer system presented at a briefing on 9 November corresponded to a southerly flight path down the middle of the wide McMurdo Sound, leaving Mount Erebus approximately 27 miles to the east. The majority of previous flights had also entered this flight plan's coordinates into their aircraft INS navigational systems and flown the McMurdo Sound route, unaware that the route flown did not correspond with the approved route.

Captain Leslie Simpson, the pilot of a previous flight on 14 November, and also present at 9 November briefing, compared the coordinates of the McMurdo TACAN navigation beacon (approximately three miles east of McMurdo NDB), and the McMurdo waypoint that the flight crew had entered into the INS, and was surprised to find a large distance between the two. After this flight, Captain Simpson advised Air New Zealand's Navigation section of the difference in positions. For reasons that were disputed, this triggered Air New Zealand's Navigation section to subsequently resolve to update the McMurdo waypoint coordinates stored in the ground computer to correspond with the coordinates of the McMurdo TACAN beacon, despite this also not corresponding with the approved route.

The Navigation section changed the McMurdo waypoint co-ordinate stored in the ground computer system at approximately 1:40 am on the morning of the flight. Crucially, the flight crew of Flight 901 was not notified of the change. The flight plan printout given to the crew on the morning of the flight, which was subsequently entered by the flight crew into the aircraft's INS, differed from the flight plan presented at 9 November briefing and from Captain Collins' map mark-ups which he had prepared the night previously. The key difference between the routes was that the flight plan presented at 9 November briefing corresponded to a track down McMurdo Sound, giving Mount Erebus a wide berth to the east, whereas the flight plan printed on the morning of the flight corresponded to a track that coincided with Mount Erebus. In contrast to the McMurdo Sound route, the updated route would result in a collision with Mount Erebus if this leg was flown at an altitude of less than 13,000 feet (4,000 m). Additionally, the computer program was altered such that the standard telex forwarded to Air Traffic Controllers at McMurdo displayed the word "McMurdo" rather than the coordinates of latitude and longitude, for the final waypoint. During the subsequent inquiry Justice Mahon concluded that this was a deliberate attempt to conceal from the United States authorities that the flight plan had been changed, and probably because it was known that the United States Air Traffic Control would lodge an objection to the new flight path.

The flight had earlier paused during the approach to McMurdo Sound to carry out a descent, via a figure-eight manoeuvre, through a gap in the low cloud base (later estimated to be at approximately 2,000 to 3,000 feet (610 to 910 m)) whilst over water to establish visual contact with surface landmarks and afford the passengers a better view. It was established that the flight crew either was unaware of or ignored the approved route's minimum safe altitude (MSA) of 16,000 feet (4,900 m) for the approach to Mount Erebus, and 6,000 feet (1,800 m) in the sector south of Mount Erebus (and then only when the cloud base was at 7,000 feet (2,100 m) or better). Photographs and news stories from previous flights showed that many of these had also been flown at levels substantially below the route's MSA. In addition, pre-flight briefings for previous flights had authorised descents to any altitude authorised by the US Air Traffic Controller at McMurdo Station. As the US ATC expected Flight 901 to follow the same route as previous flights down McMurdo Sound, and in accordance with the route waypoints previously advised by Air New Zealand to them, the ATC advised Flight 901 that it had a radar that could let them down to 1,500 feet (460 m). The aircraft was not located by the radar equipment, and the crew experienced difficulty establishing VHF communications. The distance measuring equipment (DME) did not lock onto the McMurdo Tactical Air Navigation System (TACAN) for any useful period.

|

| Wreckage of ZK-NZP |

Changes to the coordinates and departure

The crew input the coordinates into the plane's computer before they departed at 7:21 am from Auckland International Airport (now Auckland Airport). Unknown to them, the coordinates had been modified earlier that morning to correct the error introduced previously and undetected until then. The crew evidently did not check the destination waypoint against a topographical map (as did Captain Simpson on the flight of 14 November) or they would have noticed the change. These new coordinates changed the flight plan to track 27 miles (43 km) east of their understanding. The coordinates programmed the plane to overfly Mount Erebus, a 3,794 m (12,448 ft) high volcano, instead of down McMurdo Sound.

About four hours after a smooth take-off, the flight was 42 miles (68 km) away from McMurdo Station. The radio communications centre there allowed the pilots to descend to 10,000 ft (3,000 m) and to continue "visually." Air safety regulations at the time did not allow flights to descend to lower than 6,000 ft (1,800 m), even in good weather, although Air New Zealand's own travel magazine showed photographs of previous flights clearly operating below 6,000 ft (1,800 m). Collins believed the plane was over open water.

Crash into Mount Erebus

Collins told McMurdo Station that he would be dropping to 2,000 feet (610 m), at which point he switched control of the aircraft to the automated computer system. Outside there was a layer of clouds that blended with the white of the snow-covered volcano, forming a sector whiteout – there was no contrast between the two to warn the pilots. The effect was to deceive everyone on the flight deck, making them believe that the white mountainside was the Ross Ice Shelf, a huge expanse of floating ice derived from the great ice sheets of Antarctica, which was in fact now behind the mountain. As it was little understood, even by experienced polar pilots, Air New Zealand had provided no training for the flight crew on the sector whiteout phenomenon. Consequently, the crew thought they were flying along McMurdo Sound, when they were flying over Lewis Bay in front of Mt. Erebus.

At 12:49 pm, the ground proximity warning system (GPWS) began sounding a warning that the plane was dangerously close to terrain. Although Collins immediately requested go-around power, there was no time to divert the aircraft, and six seconds later the plane crashed into the side of Mount Erebus and disintegrated, instantly killing everyone on board. The accident occurred at 12:50 pm at a position of 77°25′30″S 167°27′30″E and an elevation of 1,467 feet (447 m) AMSL.

McMurdo Station attempted to contact the flight after the crash and informed Air New Zealand headquarters in Auckland that communication with the aircraft had been lost. United States search and rescue personnel were placed on standby.

Rescue and recovery

Initial search and discovery

At 2:00 pm the United States Navy released a situation report stating:

Air New Zealand Flight 901 has failed to acknowledge radio transmissions. ... One LC-130 fixed-wing aircraft and two UH-1N rotary wing aircraft are preparing to launch for SAR effort.

Data gathered at 3:43 pm was added to the situation report, stating that the visibility was 40 miles (64 km). It also stated that six aircraft had been launched to find the flight.

Flight 901 was supposed to arrive back at Christchurch at 6:05 pm for a stopover including refuelling and a crew change before completing the journey back to Auckland. Around 50 passengers were also supposed to disembark at Christchurch. Airport staff initially told the waiting families that it was usual for the flight to be slightly late but, as time went on, it became clear that something was wrong.

At 9:00 pm, about half an hour after the plane would have run out of fuel, Air New Zealand informed the press that it believed the aircraft to be lost. Rescue teams searched along the assumed flight path but found nothing. At 12:55 am the crew of a United States Navy aircraft discovered unidentified debris along the side of Mount Erebus. No survivors could be seen. At around 9:00 am, twenty hours after the crash, helicopters with search parties managed to land on the side of the mountain. They confirmed that the wreckage was that of Flight 901 and that all 237 passengers and 20 crew members had been killed. The DC-10's altitude at the time of the collision was 1,465 ft (445 m).

The vertical stabiliser section of the plane, with the koru logo clearly visible, was found in the snow. Bodies and fragments of the aircraft were flown back to Auckland for identification. The remains of 44 of the victims were not individually identified. A funeral was held for them on 22 February 1980.

Operation Overdue

The recovery effort of Flight 901 was called "Operation Overdue".

Efforts for recovery were extensive, owing in part to the pressure from Japan, as 24 passengers had been Japanese. The operation lasted until 9 December 1979, with up to 60 recovery workers on site at a time. A team of New Zealand Police officers and a Mountain Face Rescue team were dispatched on a No. 40 Squadron C-130 Hercules aircraft.

|

| One of the most difficult SAR operation ever |

The job of individual identification took many weeks, and was largely done by teams of pathologists, dentists, and police. The mortuary team was led by Inspector Jim Morgan, who collated and edited a report on the recovery operation. Record keeping had to be meticulous because of the number and fragmented state of the human remains that had to be identified to the satisfaction of the coroner. From a purely technical point of view the exercise was both innovative and highly successful, with 83% of the deceased eventually being identified, sometimes from evidence such as a finger capable of yielding a print, or keys in a pocket.

The fact that we all spent about a week camped in polar tents amid the wreckage and dead bodies, maintaining a 24-hour work schedule says it all. We split the men into two shifts (12 hours on and 12 off), and recovered with great effort all the human remains at the site. Many bodies were trapped under tons of fuselage and wings and much physical effort was required to dig them out and extract them.

Initially, there was very little water at the site and we had only one bowl between all of us to wash our hands in before eating. The water was black. In the first days on site we did not wash plates and utensils after eating but handed them on to the next shift because we were unable to wash them. I could not eat my first meal on site because it was a meat stew. Our polar clothing became covered in black human grease (a result of burns on the bodies).

We felt relieved when the first resupply of woollen gloves arrived because ours had become saturated in human grease, however, we needed the finger movement that wool gloves afforded, i.e., writing down the details of what we saw and assigning body and grid numbers to all body parts and labelling them. All bodies and body parts were photographed in situ by U.S. Navy photographers who worked with us. Also, U.S. Navy personnel helped us to lift and pack bodies into body bags which was very exhausting work.

Later, the Skua gulls were eating the bodies in front of us, causing us much mental anguish as well as destroying the chances of identifying the corpses. We tried to shoo them away but to no avail, we then threw flares, also to no avail. Because of this we had to pick up all the bodies/parts that had been bagged and create 11 large piles of human remains around the crash site in order to bury them under snow to keep the birds off. To do this we had to scoop up the top layer of snow over the crash site and bury them, only later to uncover them when the weather cleared and the helos were able to get back on the site. It was immensely exhausting work.

After we had almost completed the mission, we were trapped by bad weather and isolated. At that point, NZPO2 and I allowed the liquor that had survived the crash to be given out and we had a party (macabre, but we had to let off steam). We ran out of cigarettes, a catastrophe that caused all persons, civilians and Police on site, to hand in their personal supplies so we could dish them out equally and spin out the supply we had. As the weather cleared, the helos were able to get back and we then were able to hook the piles of bodies in cargo nets under the helicopters and they were taken to McMurdo. This was doubly exhausting because we also had to wind down the personnel numbers with each helo load and that left the remaining people with more work to do. It was exhausting uncovering the bodies and loading them and dangerous too as debris from the crash site was whipped up by the helo rotors. Risks were taken by all those involved in this work. The civilians from McDonnell Douglas, MOT and U.S. Navy personnel were first to leave and then the Police and DSIR followed. I am proud of my service and those of my colleagues on Mount Erebus.

Jim Morgan

In 2006 the New Zealand Special Service Medal (Erebus) was instituted to recognise the service of New Zealanders, and citizens of the United States of America and other countries, who were involved in the body recovery, identification, and crash investigation phases of Operation Overdue. On 5 June 2009 the New Zealand government recognised some of the Americans who assisted in Operation Overdue during a ceremony in Washington, D.C. A total of 40 Americans, mostly Navy personnel, are eligible to receive the medal.

Accident inquiries

|

| Believed to be the only photo left showing the impact |

Despite Flight 901 crashing in one of the most isolated parts of the world, evidence from the crash site was extensive. Both the cockpit voice recorder and the flight data recorder were in working order and able to be deciphered. Extensive photographic footage from the moments before the crash was available: being a sightseeing flight, most passengers were carrying cameras, from which the majority of the film could be developed.

Official accident report

The accident report compiled by New Zealand's chief inspector of air accidents, Ron Chippindale, was released on 12 June 1980. It cited pilot error as the principal cause of the accident and attributed blame to the decision of Collins to descend below the customary minimum altitude level, and to continue at that altitude when the crew was unsure of the plane's position. The customary minimum altitude prohibited descent below 6,000 ft (1,830 m) even under good weather conditions, but a combination of factors led the captain to believe the plane was over the sea (the middle of McMurdo Sound and few small low islands), and previous flight 901 pilots had regularly flown low over the area to give passengers a better view, as evidenced by photographs in Air New Zealand's own travel magazine and by first-hand accounts of personnel based on the ground at NZ's Scott Base.

Mahon Inquiry

|

| Justice Peter Mahon |

Mahon's report, released on 27 April 1981, cleared the crew of blame for the disaster. Mahon said the single, dominant and effective cause of the crash was Air New Zealand's alteration of the flight plan waypoint coordinates in the ground navigation computer without advising the crew. The new flight plan took the aircraft directly over the mountain, rather than along its flank. Due to whiteout conditions, "a malevolent trick of the polar light", the crew were unable to visually identify the mountain in front of them. Furthermore, they may have experienced a rare meteorological phenomenon called sector whiteout, which creates the visual illusion of a flat horizon far in the distance (it appeared to be a very broad gap between cloud layers allowing a view of the distant Ross Ice Shelf and beyond). Mahon noted that the flight crew, with many thousands of hours of flight time between them, had considerable experience with the extreme accuracy of the aircraft's inertial navigation system. Mahon also found that the radio communications centre at McMurdo Station had authorised Collins to descend to 1,500 ft (450 m), below the minimum safe level.

In para. 377 of his report, Mahon controversially claimed airline executives and senior (management) pilots engaged in a conspiracy to whitewash the inquiry, accusing them of "an orchestrated litany of lies" by covering up evidence and lying to investigators. Mahon found that in the original report Chippindale had a poor grasp of the flying involved in jet airline operation, as he (and the New Zealand CAA in general) was typically involved in investigating simple light aircraft crashes. Chippindale's investigation techniques were revealed as lacking in rigour, which allowed errors and avoidable gaps in knowledge to appear in reports. Consequently Chippindale entirely missed the importance of the flight plan change and the rare meteorological conditions of Antarctica. Had the pilots been informed of the flight plan change, the crash would have been avoided.

Court proceedings

Judicial review

On 20 May 1981, Air New Zealand applied to the High Court of New Zealand for judicial review of Mahon's order that it pay more than half the costs of the Mahon Inquiry, and for judicial review of some of the findings of fact Mahon had made in his report. The application was referred to the Court of Appeal, which unanimously set aside the costs order. However, the Court of Appeal, by majority, declined to go any further, and, in particular, declined to set aside Mahon's finding that members of the management of Air New Zealand had conspired to commit perjury before the Inquiry to cover up the errors of the ground staff.

Privy Council appeal

Mahon then appealed to the Privy Council in London against the Court of Appeal's decision. His findings as to the cause of the accident, namely reprogramming of the aircraft's flight plan by the ground crew who then failed to inform the flight crew, had not been challenged before the Court of Appeal, and so were not challenged before the Privy Council. His conclusion that the crash was the result of the aircrew being misdirected as to their flight path, not due to pilot error, therefore remained. But the Privy Council effectively agreed with some of the views of the minority in the Court of Appeal in concluding that Mahon had acted in breach of natural justice in making his finding of a conspiracy by Air New Zealand management. In its judgment, delivered on 20 October 1983, the Privy Council therefore dismissed Mahon's appeal. Aviation researcher John King wrote in his book New Zealand Tragedies, Aviation:

They demolished his case (Mahon's case for a cover-up) item by item, including Exhibit 164 which they said could not "be understood by any experienced pilot to be intended for the purposes of navigation" and went even further, saying there was no clear proof on which to base a finding that a plan of deception, led by the company's chief executive, had ever existed.

"Exhibit 164" was a photocopied diagram of McMurdo Sound showing a southbound flight path passing west of Ross Island and a northbound path passing the island on the east. The diagram did not extend sufficiently far south to show where, how, or even if they joined, and left the two paths disconnected. Evidence had been given to the effect that the diagram had been included in the flight crew's briefing documentation.

Legacy of the disaster

The crash of Flight 901 is one of New Zealand's three deadliest disasters – the others being the Cospatrick disaster in which 470 people died, and the 1931 Hawke's Bay earthquake, which killed 256 people. At the time of the disaster, it was the fourth-deadliest air crash of all time; as of 2014 it ranks 18th. At October 2009, the accident remained New Zealand's deadliest peacetime disaster.

Flight 901, in conjunction with the crash of American Airlines Flight 191 in Chicago six months earlier, severely hurt the reputation of the McDonnell Douglas DC-10. ZK-NZP, along with the other seven Air New Zealand DC-10s, had only just returned to service after being grounded following the crash of Flight 191 when the crash of Flight 901 occurred. Flight 901 was the third deadliest accident involving a DC-10, following Turkish Airlines Flight 981 and American Airlines Flight 191. The event marked the beginning of the end for Air New Zealand's DC-10 fleet, although there had been talk before the accident of replacing the aircraft; DC-10s were replaced by Boeing 747s from mid-1981, and the last Air New Zealand DC-10 flew in December 1982. The occurrence also spelled the end of commercially operated Antarctic sightseeing flights – Air New Zealand cancelled all its Antarctic flights after Flight 901, and Qantas suspended its Antarctic flights in February 1980, only returning on a limited basis again in 1994.

Almost all of the aircraft's wreckage still lies where it came to rest on the slopes of Mount Erebus, under a layer of snow and ice. During warm periods, when snow recedes, it is visible from the air.

A television miniseries, Erebus: The Aftermath, focusing on the investigation and the Royal Commission of Inquiry, was broadcast in New Zealand and Australia in 1988.

The phrase "an orchestrated litany of lies" entered New Zealand popular culture for some years.

Justice Mahon's report was finally tabled in Parliament by the then Minister of Transport, Maurice Williamson, in 1999.

|

| Cpt Gordon Vette |

In 2008, Justice Mahon was posthumously awarded the Jim Collins Memorial Award by the New Zealand Airline Pilots Association for exceptional contributions to air safety, "in forever changing the general approach used in transport accidents investigations world wide."

In 2009, Air New Zealand's CEO Rob Fyfe apologised to all those affected who did not receive appropriate support and compassion from the company following the incident, and unveiled a commemorative sculpture at its headquarters.

The registration of the crashed aircraft, ZK-NZP, has not been reissued.

Source:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Air_New_Zealand_Flight_901

Rescue mission over the Pacific

On 22 December 1978, a small Cessna 188 aircraft, piloted by Jay Prochnow, became lost over the Pacific Ocean. The only other aircraft in the area that was able to assist was a commercial Air New Zealand flight. After several hours of searching, the crew of the Air New Zealand flight located the lost Cessna and led it to Norfolk Island, where the plane landed safely.

The incident

Jay Prochnow, a retired US Navy pilot, was delivering a Cessna 188 from the USA to Australia. Prochnow had a colleague who was flying another Cessna 188 alongside him. The long trip would be completed in four stages. On the morning of 20 December, both pilots took off from Pago Pago. His colleague crashed on take off, but was unharmed. Prochnow landed and set out the following day to Norfolk Island.

When Prochnow arrived at the region where he believed Norfolk Island was, he was unable to see the Island. He informed Auckland Air Traffic Control (AATC), but at this point there was no immediate danger. He continued searching; after locating more homing beacons from other islands, he realised his automatic direction finder had malfunctioned and he was now lost somewhere over the Pacific Ocean. He alerted AATC and declared an emergency.

There was only one plane in the vicinity, Air New Zealand Flight 103, a McDonnell Douglas DC-10 travelling from Fiji to Auckland. The flight had 88 passengers on board. The captain was Gordon Vette, the first officer was Arthur Dovey, and the flight engineer was Gordon Brooks. Vette knew that if they did not try and help, Prochnow would almost certainly die. Vette was a navigator, and at the time of the incident he still held his licence. Furthermore, another passenger, Malcome Fortsyth, was also a navigator; when he heard about the situation he volunteered to help. As the DC-10 did not have an onboard radar, the crew had to come up with creative ways to find the lost Cessna. By this time, Prochnow had crossed the international date line, and the date was now 22 December.

Vette was able to use the setting sun to gain an approximate position of the Cessna. Then contact was established over a VHF radio which had a range of 200 nautical miles. It was hoped the DC-10 would be making a vapour trail to make it more visible. After contacting Auckland it was determined that weather conditions were not suitable for a trail. Brooks knew that by dumping fuel they could produce a vapour trail. As the search was getting more and more desperate, they decided to try it. Prochnow did not see the trail, and it was starting to get dark. Vette wanted all the passengers to be involved, so he asked them to look out of the windows and invited small groups to come to the cockpit.

As it got darker and darker, Prochnow considered ditching, but Vette did not want to give up. The crew of the DC-10 were able to use the exact moment of sunset to get a better fix on Prochnow's position. They also used a technique known as "aural boxing" to try to pinpoint the small plane; this took over an hour to complete. Once it had been done, they had a much better approximation of Prochnow's position. The DC-10 used its strobe lights to try to make itself more visible to the Cessna. It took some time, but eventually Prochnow reported seeing light. However, this was not the DC-10, it was an oil rig, and Prochnow went towards it. This was identified as Penrod, which was being towed from New Zealand to Singapore. This gave Prochnow’s exact position. After some confusion about the exact position of the Penrod, it was finally established that the estimates of the crew of the DC-10 were very accurate. Furthermore, Prochnow was probably able to make it to Norfolk Island with his remaining fuel. He touched down on Norfolk Island after being in the air for twenty-three hours and five minutes.

Events following the incident

McDonnell Douglas awarded the crew a certificate of commendation for "the highest standards of compassion, judgment and airmanship."

Jay Prochnow, a retired US Navy pilot, was delivering a Cessna 188 from the USA to Australia. Prochnow had a colleague who was flying another Cessna 188 alongside him. The long trip would be completed in four stages. On the morning of 20 December, both pilots took off from Pago Pago. His colleague crashed on take off, but was unharmed. Prochnow landed and set out the following day to Norfolk Island.

When Prochnow arrived at the region where he believed Norfolk Island was, he was unable to see the Island. He informed Auckland Air Traffic Control (AATC), but at this point there was no immediate danger. He continued searching; after locating more homing beacons from other islands, he realised his automatic direction finder had malfunctioned and he was now lost somewhere over the Pacific Ocean. He alerted AATC and declared an emergency.

There was only one plane in the vicinity, Air New Zealand Flight 103, a McDonnell Douglas DC-10 travelling from Fiji to Auckland. The flight had 88 passengers on board. The captain was Gordon Vette, the first officer was Arthur Dovey, and the flight engineer was Gordon Brooks. Vette knew that if they did not try and help, Prochnow would almost certainly die. Vette was a navigator, and at the time of the incident he still held his licence. Furthermore, another passenger, Malcome Fortsyth, was also a navigator; when he heard about the situation he volunteered to help. As the DC-10 did not have an onboard radar, the crew had to come up with creative ways to find the lost Cessna. By this time, Prochnow had crossed the international date line, and the date was now 22 December.

Vette was able to use the setting sun to gain an approximate position of the Cessna. Then contact was established over a VHF radio which had a range of 200 nautical miles. It was hoped the DC-10 would be making a vapour trail to make it more visible. After contacting Auckland it was determined that weather conditions were not suitable for a trail. Brooks knew that by dumping fuel they could produce a vapour trail. As the search was getting more and more desperate, they decided to try it. Prochnow did not see the trail, and it was starting to get dark. Vette wanted all the passengers to be involved, so he asked them to look out of the windows and invited small groups to come to the cockpit.

As it got darker and darker, Prochnow considered ditching, but Vette did not want to give up. The crew of the DC-10 were able to use the exact moment of sunset to get a better fix on Prochnow's position. They also used a technique known as "aural boxing" to try to pinpoint the small plane; this took over an hour to complete. Once it had been done, they had a much better approximation of Prochnow's position. The DC-10 used its strobe lights to try to make itself more visible to the Cessna. It took some time, but eventually Prochnow reported seeing light. However, this was not the DC-10, it was an oil rig, and Prochnow went towards it. This was identified as Penrod, which was being towed from New Zealand to Singapore. This gave Prochnow’s exact position. After some confusion about the exact position of the Penrod, it was finally established that the estimates of the crew of the DC-10 were very accurate. Furthermore, Prochnow was probably able to make it to Norfolk Island with his remaining fuel. He touched down on Norfolk Island after being in the air for twenty-three hours and five minutes.

Events following the incident

McDonnell Douglas awarded the crew a certificate of commendation for "the highest standards of compassion, judgment and airmanship."

Gordon Brooks was killed when the DC-10 operated Air New Zealand Flight 901 that he was flight engineer on crashed into Mount Erebus, Antarctica, on 28 November 1979. Vette published a book about the Flight 901 disaster, called Impact Erebus.

Source:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cessna_188_Pacific_rescue

AA 191

1979. május 25-én az American Airlines 191-es járata Chicagóból Los Angelesbe készült. Miután megkapták a felszállási engedélyt, nekikezdtek a repülőgép felgyorsításának. Az elemelési sebességig nem is volt semmi gond, ám ekkor az egyes hajtómű, és a pilonszerkezet, mely a hajtóművet a szárnyhoz rögzíti, leszakadt a szárnyról, magával rántva a belépőél egy közel egyméteres darabját. A hajtómű leszakadása révén számos életfontosságúnak bizonyuló hidraulikus ill. elektromos rendszer meghibásodott, köztük a kapitány műszerei, az átesés veszélyére figyelmeztető kormányrázó a kapitány oldalán ill. az orrsegédszárnyeltérés-érzékelők. A gépet vezető elsőtiszt műszerei, habár a gyártó által csak opcióként kínált elsőtiszti kormányrázóval nem volt felszerelve a repülőgép, továbbra is normálisan működtek. A pilóták tisztában voltak vele, hogy az egyes hajtómű leállt, de nem sejthették, hogy az leszakadt a szárnyról, hiszen a DC-10-es pilótafülkéjéből sem a szárnyak, sem a hajtóművek nem láthatók, és a toronyból sem figyelmeztette őket senki. Mivel a gép már túl volt az elhatározási sebességen, folytatták a felszállást. A gép jóval a v2 sebesség fölött, a 3km hosszú pálya kétharmadánál elemelkedett. A gép, üzemanyag- és hidraulikafolyadékcsíkot húzva maga után, folytatta az emelkedést kb. 300 láb magasságig. Hogy az elért 165 csomós légsebességüket a felszállás közbeni hajtóműhiba vészhelyzeti procedúra által előírt 153 csomós v2 sebességre csökkentsék, az elsőtiszt 14 fokig húzta a gép orrát. Mivel a hajtóműleválás megrongálta azokat a hidraulikavezetékeket, melyek a bal oldali szárny kibocsátott orrsegédszárnyait a helyükön tartják, azok a fellépő nagyfokú felhajtóerő terhelésének hatására visszahúzódtak, az ily módon létrejövő asszimetrikus felhajtóerő következtében a bal szárny átesési sebessége 124 csomóról 159 csomóra csökkent. Amint a repülőgép a v2 sebességre lassult, a bal szárny az átesés állapotába került. A gyors balra fordulást, majd az ezt követő meredek zuhanást az elsőtiszt minden igyekezetével megpróbálta ellensúlyozni, ám erőfeszítései hiábavalók voltak, a repülőgép sorsa megpecsételődött. A 191-es járat végül 112 fokos bedöntéssel, a pálya végétől mintegy másfél kilóméternyire, nyílt terepre zuhant. A nagy mennyisegű üzemanyag a becsapódás nyomán hatalmas tűzgolyóvá vált, füstjét a közel 20km-nyire fekvő Chicago belvárosából is látni lehetett. 268 utas, 13 főnyi személyzet és két, a földön tartózkodó személy vesztette életét, ezzel napjainkig az Egyesült Államok történetének legsúlyosabb amerikai földön történt repülőszerencsétlensége...

Feliratkozás:

Bejegyzések (Atom)